Of all the enterprises impacted by the growth and performance of hydraulics, it might be said that no initiative has been involved fully as much as the construction industry. From the strong excavators that are such a familiar sight at construction tasks to compact equipment that is required when building in crowded metropolitan areas, hydraulics have left their impact on construction and have completed potential feats of both engineering and architecture that would not have been possible otherwise.

Steam Power, Cables, and Winches

Earlier construction equipment, including the steam shovels that were valuable to the railroad, mining, and construction industries, used complicated mechanical systems to accomplish the motion of a shovel or bucket. These programs were comprised of gears, linkage techniques, ropes, and cables that were pushed by strong steam engines and powerful diesel engines. They were miracles of new advancements in their time and made engineering such as our first railroad networks, the Hoover Dam, and the Suez Canal likely.

First Use of Hydraulics

History shows that the first use of hydraulics in construction equipment happened back in 1882. The machine was a mixed hydraulic excavator, and while its arrival is far from what we connect with the word excavator today, it was a groundbreaking invention for its time (pun intended). It aimed to help build hull docks in England. You likely noticed the use of the word combination: fluid power (water, to be precise) was employed to actuate hydraulic sheaves for bearing power while the rest of the system was even using cables and winches. This design, yet impressive and prophetic, did not hang out to be very useful.

First Hydraulic Excavator

In 1897, the world witnessed the first fully hydraulic excavator/shovel, built by the Kilgore Machine Company. One of the advantages praised by its designers was the point that hydraulics permitted the motions to be cushioned, lowering the jar on the operator and the effect damage that the machine would inevitably participate in over time. These machines, unlike the hybrid examined earlier, were particularly useful. Now fluid force was used to dig, lift, hoist, and promise rather than manpower, which made large groups of men working with hand instruments trying to achieve an almost inhuman job.

The Expansion of Hydraulics in Construction

It was not until the 1960s that the construction industry as a whole started to switch from cables and winches to hydraulics on machines like dozers, excavators, graders, and power shovels. Once manufacturers embraced the power of hydraulic actuators and control systems, there was no looking back. This game-changing decision propelled them into a new era of efficiency and innovation! Although hydraulic systems are not easy to improve, especially in the field, they are proven to be more reliable and efficient.

And, as the technology persisted in development, hydraulics also made it likely to achieve far more specific motions (as evidenced by current videos leading excavator teeth being used to extract the lid on a bottle). Such accuracy has qualified for more optimization of specific construction methods, such as grading roads and excavating construction zones.

Hydraulically Powered Machines

When it comes to the use of hydraulics in structure, we automatically think of big machines: excavators, shovels, bulldozers, backhoes, and huge cranes. However, hydraulic systems are essential in far more machines than you might think! There are scissor lifts, trenchers, substantial pumping systems, hydraulic support cylinders, and even brick molding machines that all rely on hydraulics for their function.

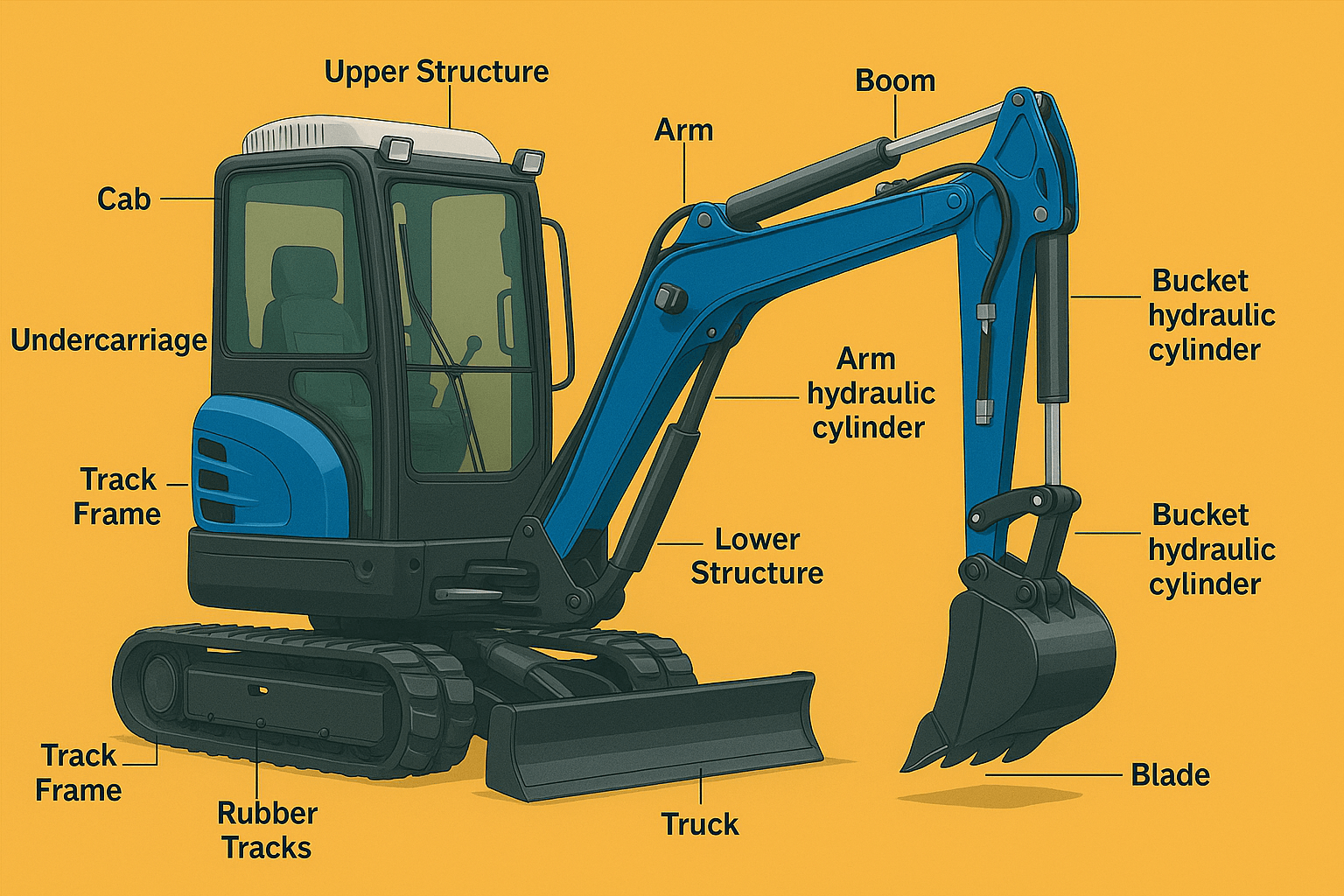

Accomplishing Powerful Motion and Accurate Control with Hydraulics

One of the key advantages of hydraulic machinery is the capability to perform motion via hydraulic actuators such as cylinders and swing motors. Via the use of numerous actuators, excessively complicated motions are made feasible. With hydraulics delivering the power after these motions, machines like excavators can drill extremely into the earth, or front loaders can scoop, lift, and deposit heavy sacks of soil or rock. And hydraulics, associated with a skilled operator, can acquire motion to an amazing breadth of accuracy. Trengraders with hydraulic systems are far more significant in precision than their cable, winch, and linkage-operated predecessors. And when hydraulics are mixed with modern technology such as grade authority, laser positioning, and GPS, the potential seems nearly eternal. The United States has already seen self-operating close track loaders made by Built Robotics at work on retail work sites in California.